Fair convex partitioning |26 September 2021|

tags: math.OC

In the  -dimensional case, the question is the following, given any integer

-dimensional case, the question is the following, given any integer  , can a convex set

, can a convex set  be divided into

be divided into  convex sets all of equal area and perimeter.

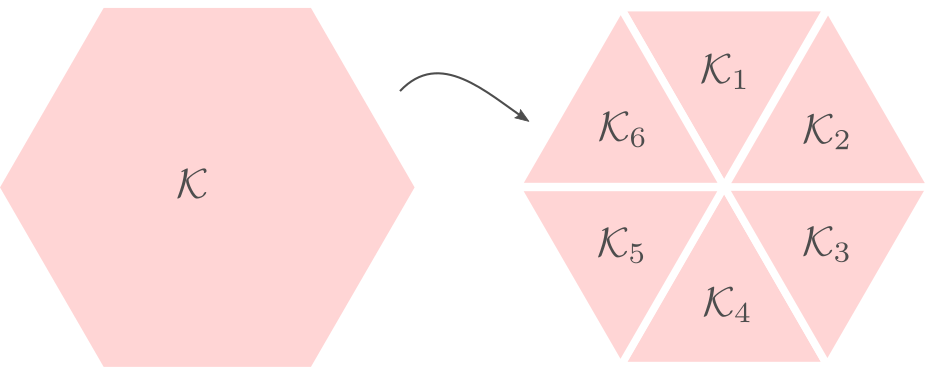

Differently put, does there exist a fair convex partitioning, see Figure 1.

convex sets all of equal area and perimeter.

Differently put, does there exist a fair convex partitioning, see Figure 1.

|

Figure 1:

A partition of |

This problem was affirmatively solved in 2018, see this paper.

As you can see, this work was updated just a few months ago. The general proof is involved, lets see if we can do the case for a compact set and  .

.

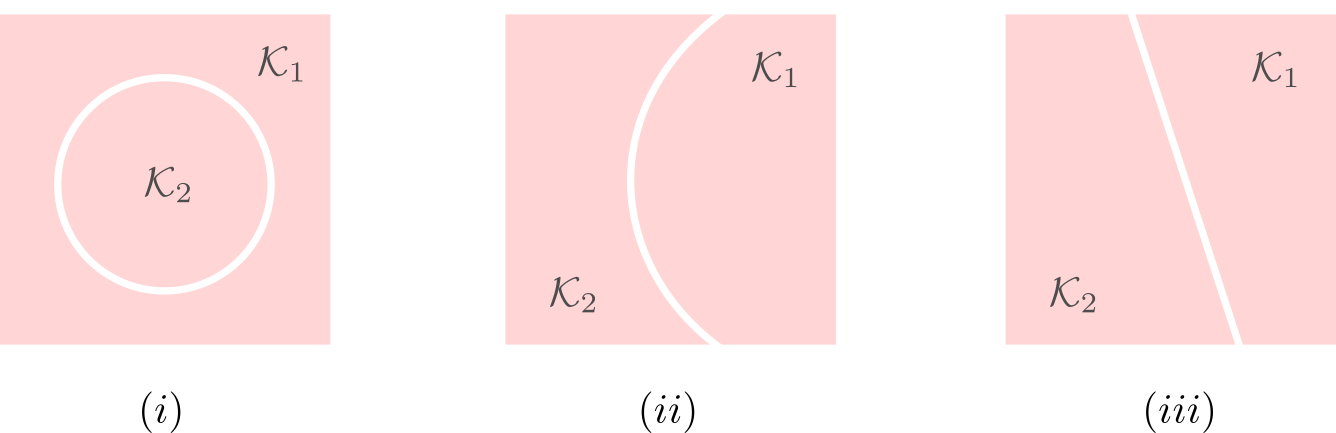

First of all, when splitting  (into just two sets) you might think of many different methods to do so. What happens when the line is curved? The answer is that when the line is curved, one of the resulting sets must be non-convex, compare the options in Figure 2.

(into just two sets) you might think of many different methods to do so. What happens when the line is curved? The answer is that when the line is curved, one of the resulting sets must be non-convex, compare the options in Figure 2.

|

Figure 2:

A partitioning of the square in |

This observation is particularly useful as it implies we only need to look at two points on the boundary of  (and the line between them). As

(and the line between them). As  is compact we can always select a cut such that the resulting perimeters of

is compact we can always select a cut such that the resulting perimeters of  and

and  are equal.

are equal.

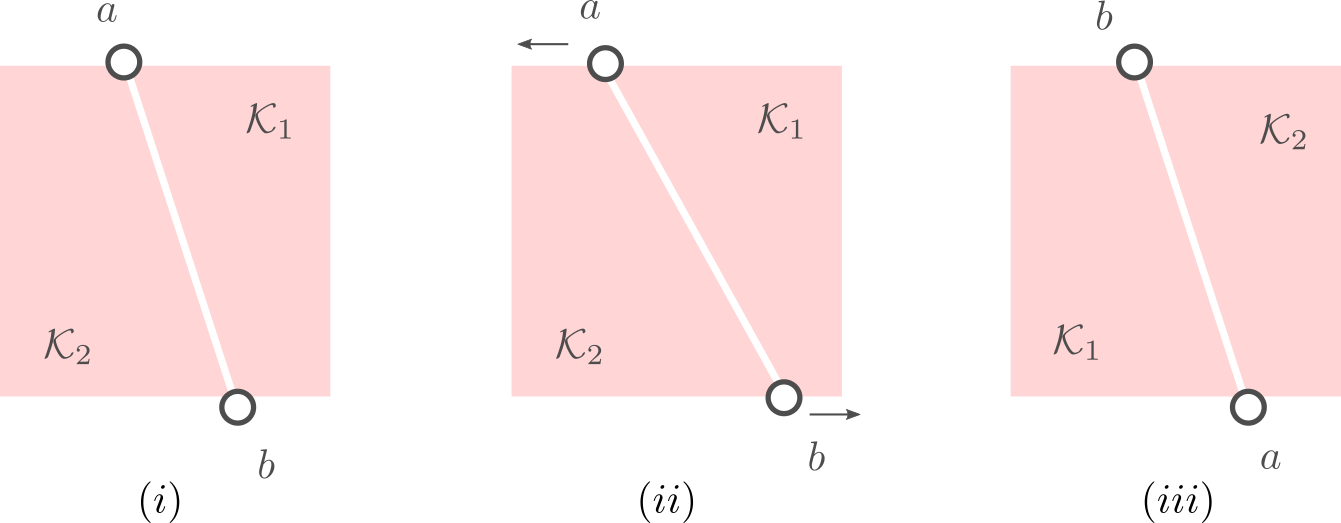

Let us assume that the points  and

and  in Figure 3.(i) are like that. If we start moving them around with equal speed, the resulting perimeters remain fixed. Better yet, as the cut is a straight-line, the volumes (area) of the resulting set

in Figure 3.(i) are like that. If we start moving them around with equal speed, the resulting perimeters remain fixed. Better yet, as the cut is a straight-line, the volumes (area) of the resulting set  and

and  change continuously. Now the result follows from the Intermediate Value Theorem and seeing that we can flip the meaning of

change continuously. Now the result follows from the Intermediate Value Theorem and seeing that we can flip the meaning of  and

and  , see Figure 3.(iii).

, see Figure 3.(iii).

|

Figure 3:

By moving the points |

fair convex sets.

fair convex sets. into two convex sets can only be done via a straight cut.

into two convex sets can only be done via a straight cut.